On Sunday next, members of our Club Executive Committee, representing the wider club, will make the short journey to Bluebell Cemetery to place a wreath at the grave of Joseph Traynor as a mark of respect on what is a momentous weekend for the GAA.

So who was Joseph Traynor and what type of Ireland did he grow up in?

Well if like Willie Kennedy, one of our U10 boys coaches, you happened to grow up in Ballymount, (the area behind the Red Cow to relative newcomers to the ‘Towers family’!) you would probably have grown up listening to stories to how Joseph or ‘Joe’ went to Croke Park like so many of us on a given Sunday – but crucially, never came home.

Of course, it wasn’t just any given Sunday – it was a day that would become forged in the Irish psyche taking on the moniker of ‘Bloody Sunday’, when 14 people attended a challenge match on Jones’ Road and never returned home afterwards.

On Sunday November 21, 1920, Ireland was in a state of turmoil.

The War of Independence raged between the forces of the Crown, namely the Black and Tans and the Auxiliaries, but also the Royal Irish Constabulary, and the Irish Republican Army who were challenging British rule in Ireland by means of physical force and guerrilla warfare.

While Dublin, the seat of British power in Ireland, did not experience the same level of fighting compared to areas of Munster in particular, British intelligence successes were beginning to thwart the IRA’s ability to wage a war and Michael Collins moved to address this.

On the morning of the game, his carefully selected ‘Squad’ targeted British agents who had become known as the ‘Cairo Gang’ owing to one of the café’s they frequented.

Their assassinations were clinical and brutal and the activities sent shockwaves across the British Administration and throughout Dublin and indeed Ireland as a whole.

Anxiety hung over the city that day with a challenge football match between two of the game’s top teams, Dublin and Tipperary, scheduled to take place at Croke Park that afternoon.

The GAA faced a dilemma; proceed with the game as planned or postpone the match and expose the organisation to accusations of being some way complicit in what had unfolded earlier that morning.

As we all know, the game went ahead – delayed – lasting no more than 15 minutes and remaining scoreless, before security forces arrived at the scene giving rise to scenes of chaos and eventually carnage with wild shooting lasting no more than 90 seconds.

When it ended 13 people lay dead and another would lose their life in the days that followed.

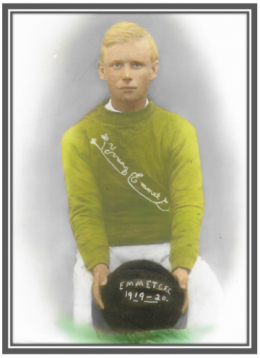

Joseph Traynor

Work by Joe’s nephew Micheál Nelson, a son of Bridget ‘Ciss’ Traynor (Joe’s sister), gives us an idea of the young life lived by Joseph and the tragic circumstances of the fateful day.

Born on St Patrick’s Day in 1900 to Kate and Michael, originally from Aughrim in Co. Wicklow, the family initially lived at Drimnagh Castle before it was sold and they relocated to Ballymount, close to where the existing intersection between the N7 and M50 is now located.

Joe went to school in Clondalkin, at the Carmelite Mt. St. Joseph’s school known locally as ‘The Monastery’. The school site and its remains are located only yards from the entrance to the club grounds at Monastery Road adjacent to where houses are now located at Monastery Gate Heath.

The school was located on the road between the Red Cow and Clondalkin Village.

Joe was described as an outgoing young man and by 1920 he had become captain of the ‘Young Emmets’ GAA Club, based in nearby Fox and Geese, a club no longer in existence.

He was employed at Cullen’s Farm and would have celebrated his 21st birthday the following March.

He was active in the national movement of the time.

News of the morning’s happenings on the day of the game would not have been as widely known as they might be today, given limited communication sources, and Joe and his friends headed for Croke Park like so many of groups of young people still do to this day.

They entered the ground at the Russell St turnstiles and took up positions at the Canal End, which is now known as the Davin Stand, settling behind the goal.

When the shooting started supporters in this end of the ground began to scramble to safety, many attempting to scale a wall at this end of the ground. These people became the target of the shooting and Joe was shot twice in the back and found slumped on a pathway behind the stadium adjacent to Sackville Gardens.

Joe was pronounced dead an hour after being admitted to Jervis St hospital and it was his father who identified him. He was buried the following day at Bluebell Cemetery on the Old Naas Road where is family have lovingly maintained his impressive grave, a stand out Celtic Cross, refurbished for the 100 year commemoration.

The murder of the day did not finish at Croke Park. Dick McKee, Peadar Clancy and Conor Clune – a young man in the wrong place at the wrong time – all lost their lives in British captivity that evening. The British administration claimed they were killed attempting to escape.

The wounds to their bodies suggested something different unfolded.

The aftermath

The events of that fateful day in many ways added further fuel to a raging the conflict. The slain innocents at a sporting occasion made international headlines and after being debated in the House of Commons in London commissions of enquiry followed.

With no public element to them, it was in essence a case of the military investigating themselves and this coloured the willingness of many of the families to fully engage with charade.

Unlike the high profile funerals in England for the soldiers killed on the morning of Bloody Sunday, the authorities in Ireland warned that there was to be no public element to the funeral arrangements of those killed in Ireland.

Some were buried in the lowest key manner imaginable and other buried in unmarked graves.

In more recent times the GAA assisted a number of families to erect and repairs gravestone at the resting place of the deceased.

The impact today

While the victims’ loss and the mourning of them remains most sorely felt by the families, Bloody Sunday is an important part of the GAA’s own story.

The fledgling organisation (founded in 1884 like Round Tower GAA Club), would never be quite the same again.

Similarly, Croke Park took on a whole new meaning as the primary stadium of the organisation.

It became more than a field and more than a venue and it is often cited as one of the reasons why the GAA never realistically considered calling anywhere else home.

Those ties between the stadium and the wider organisation remain as strong today as they ever have and on Saturday evening (November 21), despite the absence of supporters, the GAA will honour those who were murdered and acknowledge their families.

Go dtuga Dia suaimhneas síoraí dá n-anamacha.

*Special thanks to Micheál Nelson on behalf of the Traynor Family for his engagement and the supply of information for this article.

Alan Mac Maoldúin / Stiúrthóir Cumarsáide CLGAlan Milton / GAA Director of Communications